The Danger of Being Religious

A deeply religious person is not necessarily a good human being. While religion can inspire some people to be their very best selves, other religious people retain their vices but then justify their behavior as sanctioned by their selectively chosen religious convictions.

While I’m sure there are many reasons for the polar opposite responses to religious belief—psychological, intellectual, and cultural being just a few—I think religious people, both those who become better people as well as those who double-down on their misguided behavior, believe they enjoy an intimacy with God that other people simply don’t have.

If people believe they have a relationship with God that non-believers don’t have, those feelings can easily morph into the belief that how they feel about right and wrong is how God feels. Their presumed closeness to God allows them to assume their thoughts are God’s thoughts and their politics are God’s politics.

Not all people of faith believe that their relationship with God places them on the same wave length as God. For those who take the time to read the Bible they learn that God’s thoughts are not at all our thoughts (Isa. 55:8-9). Nevertheless, when we enter into a relationship with God by faith, if we’re not continually second-guessing ourselves and enlarging our circle of understanding, we can fool ourselves into thinking that our beliefs are in sync with God’s and those outside the faith are inferior, less deserving, or less knowledgeable. Consequently, human nature, being what it is, we can readily convince ourselves that God’s favor implies God’s approval for whatever we say or do in his name.

Now, few people would ever verbalize feelings of superiority. In fact, a healthy religious belief recognizes that we are all spiritual beggars and even the best of us have nothing to crow about. Words like grace, mercy, and love explain a person’s relationship with God and many people of faith will quickly admit they are works in progress. A Christ follower, in other words, believes he has a spiritual relationship with the Almighty, but also acknowledges there is an ongoing battle to put to rest any feelings that his standing with God is deserved or places him on a pedestal above others or allows him to read the mind of God.

Israel struggled its entire biblical history to come to terms with what it meant to be in relationship with God. From its earliest memories, Israel believed that God had selected them out of all the nations of the earth. They derived their special status from Genesis 12, which reveals that God chose Abraham and his descendants to be his chosen people. That’s heady stuff and Israel has grappled with spiritual hubris and feelings that they were better than other nations throughout their existence.

So, what does it mean to be in special relationship with God? Without boring you with a lot of Old Testament theology and Hebrew grammar, the Old Testament word “choose” or “elect” in Genesis 12 and elsewhere implies the idea that Israel’s unique blessing requires accountability. Israel was not chosen because they were better or spiritually superior to other nations, and they were certainly not chosen to the exclusion of others. They were chosen to tell the world that God invites everyone to the table. No one was to be left out. God loves not just Israel but all nations.

The Bible stresses that Israel’s blessing entailed a specific duty and would be lost if Israel failed to share the blessing. Whenever God’s blessing became a source of pride and arrogance, and they grew full of themselves with attitudes of superiority or sought dominance over others, the prophets warned the people they were not in any way more deserving than non-believers. As a case in point, a non-believer’s conduct might very well be more noble and praiseworthy than that of God’s people (See Gen. 12:10-20; 26:1-11; also Matt. 8:5-10 and Lk. 7:1-9).

God’s blessing was not for Israel’s comfort and security but involved suffering and humiliation. Israel’s blessing meant that God’s people would be servants and witnesses, not Lords and Masters. They were most decidedly not called to control or dominate others; rather they were to humbly serve as bridges between God and the world.

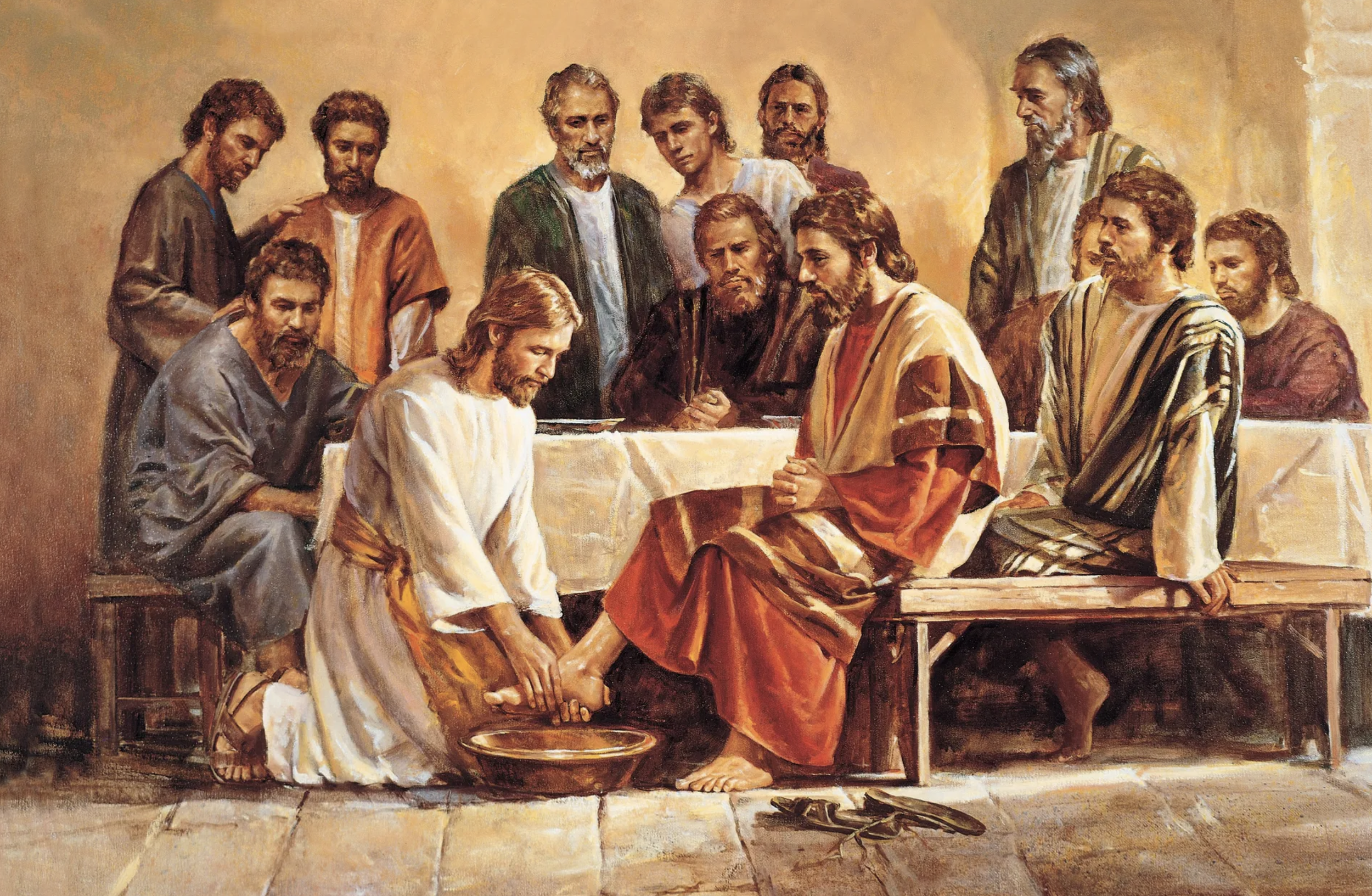

Jesus reiterated the Old Testament’s emphasis that God’s people are to be characterized by humility and servanthood, not power and domination.

Whoever wishes to become great among

you shall be your servant; and whoever

wishes to be first among you shall be slave

of all. For even the Son of Man did not come

to be served, but to serve and to give his life

as a ransom for many.

(Mark 10:43-45)

When religious people get confused about their role in the world and begin to drift toward feelings of arrogance and a desire for control, their worst instincts and darker powers surface. We have seen deluded behavior from groups like the Ku Klux Klan and more recently by the so-called Christian Nationalists.

Anthea Butler, chair of the department of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania, writes, “Christian Nationalists place love of country and political power over God and assume that God favors one nation over others,” which misunderstands completely what it means to be a Christ-follower. Consequently, there is little of Christ in Christian Nationalism and this nationalistic horror film has been played throughout history in the Crusades, Inquisitions, Islamic extremists, Buddhist nationalists persecuting Rohingya Muslims, and by so many other nationalistic religions.

Anthea Butler

While Christian nationalists brag about fighting for Jesus, they fail to follow his teachings. Jesus practiced love for all people, regardless of their religion, nationality, or ethnicity. Jesus chose the way of servanthood and the way of the cross. Christian Nationalists look at Jesus on the cross and say, “You know what? I think I’ll do it my way!” That’s when religion becomes evil.

Why do you call me ‘Lord, Lord,’ and do

not do what I say?

(Jesus)