What’s the Use of a College Degree?

Scrolling through Instagram one afternoon, something I seldom do, cartoon-like images of two young men caught my attention, one a philosopher and the other an electrician. The philosopher, surrounded by his books, appeared harried, bewildered, and desperate. His electricity was being cut-off, and he was obviously in financial distress. The implication was clear that his work as an academic didn’t pay well, and, on top of that, he owed tens of thousands of dollars in student loans.

The electrician, on the other hand, was in the process of cutting off the philosopher’s electricity. The caption noted that he was paid a stipend even while learning his craft and was now earning over $100,000 a year as a full-time electrician.

The message I took away from these images was that not only does a college education leave one in debt, but an academic career is a financial dead-end. In the meanwhile, vocational training has benefits from the moment one begins as an apprentice and offers a financially rewarding life. In short, why in the world would anyone want an academic career?

Now, I’m a proponent of vocational training. I wish more high schools offered opportunities for students to apprentice with companies that train workers in practical skills, like plumbing, electrician training, welding, carpentry, and so much more. In Europe, these jobs are highly valued and offer significant financial benefits for young people who choose not to go the college route.

The Instagram images, though, were also misleading. While vocational training is incredibly important and should be highly prized, an academic career is indispensable as well. Would you trust an airplane that only had one wing? Or how secure would you feel on a plane flying across the Atlantic that had lost one of its engines? Our country needs both the highly skilled vocational craftsman and the highly trained academic. Neither should be disparaged.

It does a disservice to our country when academics are put down as people who are out of touch with the main stream and contribute little to our society. Philosophers, historians, teachers, and the humanities in general are viewed by many in the public sphere as meaningless professions that have little practical value. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Western civilization has been built on the contributions and insights of philosophers and scientists. True, they are often undervalued and underpaid in our culture, and that is tragic, but their importance can hardly be overestimated. So many of the vocational fields are dependent on the discoveries and innovations by the academic community.

Western science began with the Greek philosophers hundreds of years before Jesus was born. The philosophers focused on various aspects of human life, such as logic (what is true), physics (the nature of existence), and ethics (the best way for human beings to achieve happiness and well-being). The Greek philosophers valued reason over superstition and introduced rational explanations for phenomena like earthquakes, eclipses, and diseases. Such events like thunder were not the actions of the gods but natural occurrences in nature, according to the first philosophers.

Euclid, who taught in Alexandria around 300 B.C., made discoveries in two-and-three dimensional space. Euclidean geometry continues to be utilized to this day. The philosopher Archimedes calculated the approximate value of pi and devised a way to work with extremely large numbers. He also invented hydrostatics (the science of the equilibrium of a fluid system), and mechanical devices such as the screw for lifting water to a higher elevation.

Euclid

Aristarchus, in the early 3rd century B.C., theorized the heliocentric universe. His theory was rejected, however, because he postulated circular orbits for the planets instead of elliptical. The circular orbits presented mathematical problems in calculating planetary motion and was therefore put aside by astronomers. Another eighteen hundred years would pass before the Polish astronomer Copernicus would prove Aristarchus’ heliocentric theory correct by using elliptical patterns for the planets instead of circular. Aristarchus also built a working water pump, and the first working water clock.

Aristarchus

Eratosthenes (275-194 B.C.) estimated the circumference of the earth with amazing accuracy. Not until relatively modern times did scientists provide more accurate numbers.

The Pharos lighthouse in Alexandria (280 B.C.) was three hundred feet tall and is considered one of the wonders of the ancient world. Using polished metal mirrors to reflect the light from a large wood fire, it shone far out to sea, guiding sailors into port.

The ancient world may not have had the technology of today, but they were by no means primitive. Precise scientific experimentation did not exist in Greece because they did not have the technology for precise measurement. Still, a spirit of scientific and philosophic invention prevailed in spite of these technological difficulties.

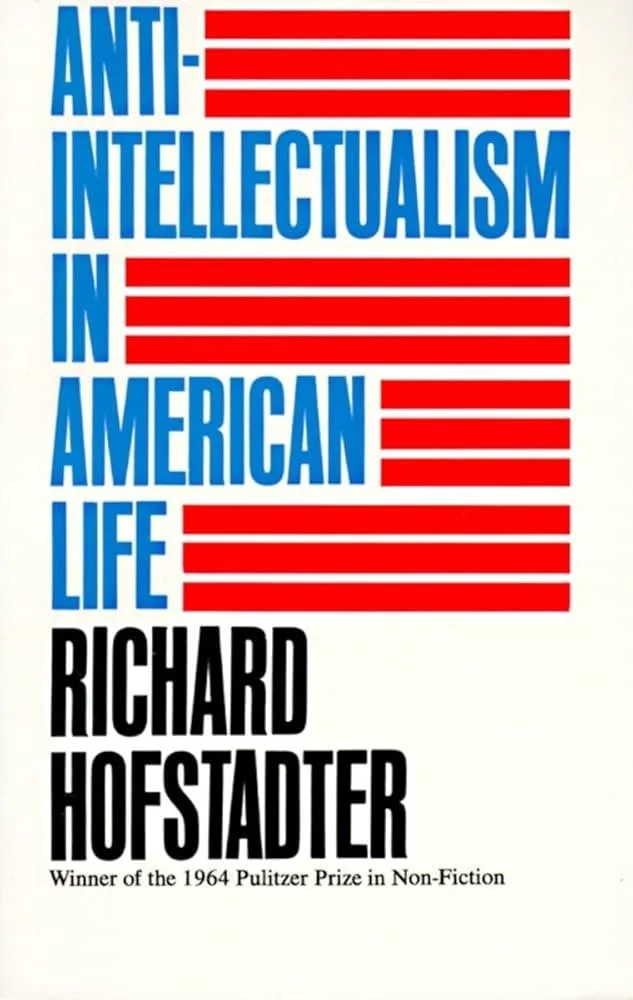

Richard Hofstadter’s Pulitzer Prize 1964 book Anti-Intellectualism in America points out how Americans have too frequently dismissed intellectual pursuits in favor of more practical endeavors. That’s understandable given our history. When people first came to America, immediate concerns dominated the settler’s lives—food, shelter, earning a living. There wasn’t time for higher education, research, innovation and more abstract pursuits by most early pioneers.

Thankfully, there were philosophical and scientific Americans who made time for discovery. Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, David Rittenhouse (astronomer and mathematician), Charles Willson Peale (natural history), Josiah Royce (philosopher), Charles Sanders Peirce (founder of American pragmatism), John Dewey (educator), and the list goes on and on. Each of these philosophers, scientists, and educators made lasting contributions to American intellectualism. Without these notable and highly educated minds how impoverished our nation and world would be.

Our modern way of life relies on both the professional academic as well as the vocational craftsman. Perhaps they are not equally valued in our culture today, but our country needs both wings to fly. Maybe next time, the electrician will leave the lights on!